Soil formation, composition and analysis

We forget that there was a time… without soil! Indeed, without plants, no thick soil can really form. And yet, plants only appeared on Earth 470 million years ago…

In the absence of soils, composed of plant debris and minerals, which retain water from precipitation, runoff is intense and rapid. Without soils to support plant growth, animals cannot survive on the Earth’s surface either…

Soils are essential to terrestrial ecosystems as we know them today. They are an integral part of our landscapes, nourish us through agriculture, and we tread on them every day without even noticing! But what is soil? How is it formed, and what elements make it up? How is soil analyzed, and why?

This page takes you underground, to the heart of soil minerals, right beneath our feet, before discovering more, why not, at Minerallium, the Fonds de Dotation Roullier exhibition, presenting the role of minerals in plant, animal and human nutrition.

Definition and importance of soil mineralogy in the study of ecosystems

What does soil consist of? In temperate climates, minerals are the main component of soil (around 95%), while organic matter (humus) on the surface represents only 1 to 5% at most. These minerals come either from the bedrock on which the soil has developed (most often feldspars, micas and quartz), or from the transformation of pre-existing minerals, such as iron oxides and hydroxides, or clays.

The physical and chemical properties of minerals regulate various soil functions. Because of their nature and organization in space, they enable the soil to store water reserves, which are then useful for soil life. The elements contained in the various minerals also constitute nutrient reserves for the living beings that populate the soil: bacteria, fungi and, of course, plants!

Soil formation and mineral composition

Our soils were not created overnight: Soil formation is a long-term process! In our temperate climates, it is estimated that the rate of soil formation is approximately one centimetre per century. It therefore takes around 10,000 years to obtain a soil depth of one meter, which corresponds to the average for our regions. However, the phenomenon of soil thickening is more pronounced in hot, humid tropical climates, which are home to more intense microbial life, enabling faster decomposition of plant debris and greater production of organic matter.

How is soil formed ?

The first stage is the chemical and physical alteration of bedrock, from the surface, by meteorological phenomena such as rain, frost and wind, but also by living beings, such as bacteria and fungi. Microbes are also rock miners. They capture the mineral salts they need for their cells and roots: potassium, phosphorus, calcium, iron…

Plants are also very active in this process via root growth, as they are avid consumers of rock dissolution products. Rock fragmentation provides them with mineral elements such as phosphorus, potassium, magnesium and calcium, which are essential for their growth. Roots therefore proliferate in areas where dissolution takes place and where water is richest.

Soil Formation Process

The process of soil formation occurs in several stages. Over time, successive organisms settle and modify the environment for their followers, who could not establish themselves without the physical and chemical alterations produced by their predecessors. The stages are as follows:

- A microbial biofilm initially forms on the bare rock. The first arrivals are often photosynthetic organisms, microscopic algae, and cyanobacteria, followed by other microbes, bacteria, and fungi that feed on their predecessors or their waste. These microbes often live in biofilms combining multiple species. This biofilm already attacks components of the rock and retains water, dead organic matter, and mineral fragments.

- The amount of soil formed from organic matter debris created by the microbial biofilm is minimal, but it is sufficient, after a while, to nourish a root system. The so-called “pioneer plants” then settle, which are a few sparse annual plants.

- As time passes, the mass of pioneer plants increases, and more diverse species with larger and more durable vegetative development settle. This development is enabled by the progressive thickening of the soil through the accumulation of organic matter from dead plants and microbes.

- This thickening of the soil, in turn, allows the installation of the first shrubs. These bring even more organic matter and retain thicker soil thanks to their more developed root system. This thickening soil is very black because the abundance of calcium forms aggregates called the clay-humus complex.

- The succession continues with denser bushes, then thickets, forming a 1 to 3-meter-high growth called a fruticetum. This often includes species like blackberry, hawthorn, blackthorn, and wild cherry. Underground, the soil has thickened up to 1 meter. It turns brown towards the surface because calcium is washed downwards by rainwater and replaced by iron, released by the rock’s attack, within the clay-humus complex.

- After decades, a forest settles. The soil has become thick enough to support and nourish the roots, which in turn hold it over more than a meter. The succession is then complete. The soil’s color is browner than ever because calcium continues to disappear into the depths: this particular type of soil is called “brunisol,” named after its color. However, the soil no longer thickens: the attack on the parent rock is very slow, and its progress is now equal to erosion. This endpoint is called the climax of the soil.

The influence of minerals on soil formation

Altered bedrock – the surface layer of the earth’s crust composed of different types of minerals – forms the basis of all soils. This bedrock can be of three different types: magmatic rock, i.e. magma that has solidified; sedimentary rock, resulting from the accumulation of various sediments over time; or metamorphic rock, resulting from the transformation of the other two types of rock.

The process of soil creation is essentially the same, whatever the nature of the parent rock: limestone, granite, schist, sand or clay. Indeed, although the mineralogical composition of the bedrock and its type of alteration are important in the formation and evolution of soils, they are secondary to climatic conditions, via water supply and temperature, and to the type of vegetation that covers them. The same stages of creation then follow one another.

There are, however, slight differences: for example, in the absence of limestone, whose carbonates make the soil neutral, the soil immediately becomes more acidic (as is the case with granite-based soils in Brittany). However, as the soil becomes deeper and deeper, the distance to the bedrock increases, limiting its influence, and we tend to find the same type of soil everywhere in our temperate climate: brown leached soil, more or less acidic.

Soil mineral composition

Mature soil is composed of differentiated superimposed layers, called horizons. These layers differ in appearance, mineralogical composition and structure. The soil profile is made up of these different horizons, designated by letters. It generally comprises, from top to bottom :

- The O horizon, at the very top, which contains only organic matter that has fallen to the surface.

- The A horizon, below, is mixed with mineral elements and organic matter.

- The B horizon receives elements leached from the A horizon (notably mineral elements such as calcium from the clay-humus complex).

- Finally comes the almost pure mineral matter, with the exception of a few microbes and a few alterations: the C horizon, made up of altered bedrock.

It would be impossible to provide an exhaustive overview of the various mineral elements present in soil. Indeed, while a rock is composed of one or more assembled minerals, soils often contain far more than the parent rock because they receive minerals from it and those formed in the soil through the alteration of pre-existing minerals. Thus, soils harbor an extraordinary mineral composition: more than half of the mineral species known in nature.

We have seen that soil minerals come from the physical and chemical weathering of the parent rock and the reorganization of elements from it, mainly due to the action of climate and soil microbes. However, there is another significant source of mineralization that has not been discussed until now: the decomposition of organic matter, or humus, which forms the upper layer of the soil.

Indeed, the soil constantly ingests and digests organic matter from plant and animal debris. While these contain a lot of CO2, lignin, and cellulose, some mineral elements, representing approximately 10% of the total, are also present in the remains of dead cells: nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur, etc. Bacteria and fungi decompose these elements, notably with the help of enzymes. Part of the product of this decomposition is then re-mineralized through the energy production of organisms and subsequently released into the environment in a form that plants can assimilate.

Classification of Soil Minerals

Soil often contains particles of all sizes mixed together. These particles have different properties, providing various benefits for soil organisms and plants. The largest elements, measuring over 2 mm, are the ones we know best because their size makes them highly visible: these are rocks.

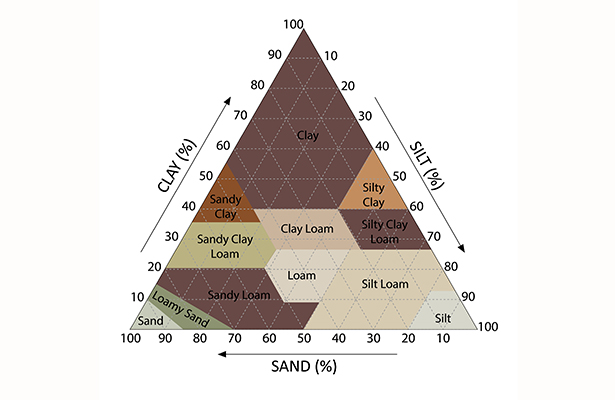

Fragments smaller than 2 mm are the ones soil scientists—pedologists—use to define the nature of a soil. They are classified into three categories:

- From 2 to 0.050 millimeters, these fragments are called sands.

- Between 0.050 and 0.002 millimeters, they are called silts.

- Below 0.002 millimeters, they are referred to as clays.

The words “sands” and “clays” here refer to sizes, not mineral composition: this is called soil texture. When one of the classes dominates, the soil is described as sandy, clayey, or silty. When two fractions dominate, we refer to the soil as sandy-silty or silty-clayey, for example. This definition will result in particular chemical and physical properties of the soil that must be considered for cultivation (appropriate crops, soil care, etc.).

From an agronomic perspective, do we prefer sandy, silty, or clayey soil? In reality, we quickly realize that each of these classes is detrimental when present in excess, while their mixture is beneficial:

- Rocks, blocks, and sands all have in common that they create large spaces between them, allowing water and air to pass through, which is important for soil life.

- However, it is not enough for water to pass through; it also needs to be retained: silts and clays, on the other hand, retain water in the soil by creating smaller spaces.

- However, too much clay can hold water too tightly, making it inaccessible to living organisms, especially roots.

- Silts have a different negative effect: in excessive amounts, they are prone to compaction. On bare or plowed soil, they reorganize and compress into a crust, called a surface crust, which slows the entry of air and water into the soil.

Thus, a balanced presence of sands, silts, and clays creates soil fertility. The balance of these fractions also depends on the climate: in rainy areas where drainage is vital, more sands might be preferred, for example.

Soil Mineral Analysis

Soil analyses are now commonly practiced in agriculture, with nearly 300,000 conducted each year in France. These analyses provide data to understand the structure and fertility of soil, enabling the adaptation of farming practices, the type of fertilization to be applied, and the optimization of crop strategies. A comprehensive soil analysis revolves around four parameters: texture, acidity (which helps characterize the Cation Exchange Capacity), organic profile, and the mineral status of the soil.

How is such an analysis conducted? Soil samples are collected in the field by coring at different locations on the plot, and then these samples are analyzed in a laboratory. Soil analyses are highly regulated. Each year, sometimes several times a year, the Ministry of Agriculture publishes an official list of accredited soil analysis laboratories. A mineral status analysis of the soil is then performed, often including the measurement of primary and secondary essential mineral elements for crops: phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, calcium, iron, copper, manganese, boron, and sulfur, as well as the soil’s nitrogen content.

These measurements are performed using different techniques depending on the element being sought. First, the soil is dried and sieved, freeing it from plant debris and stones. The processes can then be chemical or mechanical, with various steps in succession: extraction of elements from the soil by an extraction agent, dissolution of minerals, and then the addition of a reagent, for example. The results can also vary depending on the form in which the element is present in the soil. For example, phosphorus can be present in several forms, and each method can only capture part of it: thus, there are both “hot” and “cold” extraction procedures for phosphorus, which are complementary.

What is the agronomic benefit of these analyses? Each element occupies a specific role in the development of a particular crop, some being more important depending on the growth stage or the development of a given plant species (for example, rapeseed has particularly high requirements for sulfur and boron). Furthermore, a deficiency in a single element can prevent other elements, even if present in the soil, from being assimilable by the plant. Therefore, it is essential to know the mineral content of your soil to address potential deficiencies that could hinder crop development and reduce yields.

However, this analysis of the mineral state of the soil, while important in itself, appears inseparable from the three other analyses performed (texture, acidity, and organic profile). Indeed, these four parameters form a whole that allows us to understand how a particular soil functions and how the crops planted there react, providing all the keys to maintaining perfectly healthy soil.

Roles of Minerals in Soils

In the soil, minerals provide nourishment for the organisms living there: plants, of course, but also certain bacteria that feed directly on the minerals contained in the rock.

For a plant to grow, it needs water, light, and… obviously, minerals! It is in the soil that it exclusively extracts primary minerals (phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, calcium, sulfur, and iron) and secondary minerals (manganese, zinc, copper, boron, and molybdenum) that are essential for its growth. What are the necessary quantities?

For example, one hectare of vineyard requires 200g of boron, 180g of copper, 600g of iron, 300g of manganese, 4g of molybdenum, and 250g of zinc annually… which is nothing compared to the 8kg of phosphorus, 67kg of potassium, and approximately 15kg each of magnesium and calcium it needs. Therefore, the plant must extract these elements from the soil through its roots. This is one of the reasons why one-third of the plant’s biomass is underground!

But microbes are also rock miners. They capture in the soils the mineral salts necessary for their cells, similar to roots: primarily potassium, phosphate, calcium, or iron. They feed on these mineral elements resulting from the degradation of the rock, but some can also use them as an energy source. These bacteria are called “chemolithotrophs.” The chemical reactions they carry out release the energy they need to live while producing more oxidized forms of minerals that have reacted with oxygen.

Moreover, certain mineral elements, such as calcium (Ca2+) and iron (Fe3+), play an important role in the formation of the clay-humus complex, where clays and organic matter are bound together. By binding with organic matter particles in the soil, calcium and iron form the clay-humus complex, which has a threefold agronomic benefit: its mineral and organic elements, being heavier, are less easily leached by water and therefore remain in the soil longer; they mutually protect each other; and they promote a porous soil structure that allows air entry and water retention.

Practical Application of Soil Mineralogy

The mineralogical study of soils allows for precise knowledge of the different mineral elements present in the soil. In an agricultural context, this study is extremely important: it provides the opportunity to know exactly, based on the potential of each soil and the specific needs of each type of crop, how much mineral elements need to be added to optimize agricultural yields.

Indeed, with each harvest (whether cereals, fruits, or vegetable crops, etc.), mineral elements are removed from the agricultural plot. If these losses are not compensated in some way, the soil becomes impoverished over time, and its fertility decreases. These mineral losses can be corrected by various methods: mineral or organic fertilizers, fallows, nitrogen-fixing cover crops, etc., each having its advantages and disadvantages.

Thanks to the mineralogical study of soils, the supply of minerals to crops can be carried out in a rational manner, taking into account the actual needs. Mineral resources on our planet are not unlimited and must be used sparingly. For example, many soils in Western Europe currently contain several decades of phosphorus reserves, as phosphates spread over time have crystallized and are released slowly. This allows minimizing inputs as much as possible, considering that the world’s known phosphate mineral reserves are expected to be exhausted within a hundred years at the current rate of extraction.

Conclusion

Providers of nourishment for plants, microorganisms, and consequently all terrestrial animals, soil minerals appear as the cornerstone for maintaining life on our planet!

Alongside this nourishing function, soils also have other crucial roles: influencing the climate (carbon storage in the soil to combat global warming, thermal insulation, for example), serving as a reservoir of biodiversity, and being an essential link in the Earth’s water cycle. The role of soil and its minerals is ecosystemic, providing us with food, materials, energy, and more. Therefore, it is essential to preserve our soils—a collective resource that concerns us all—from degradation and to maintain or restore their potential for sustaining life and nutrition for living beings.